Hosts Rick Potestio (center) and Jonathan Konkol (right) with the low-density building table in the foreground. (Lisa Caballero/BikePortland)

Hosts Rick Potestio (center) and Jonathan Konkol (right) with the low-density building table in the foreground. (Lisa Caballero/BikePortland)

Game on!

Armed with only a bag of legos and a table-sized map of district properties, you and your team have a couple hours to insert 600 new residences into Portland’s historic Irvington neighborhood.

The group which gathered last Saturday at the Broadway McMenamins seemed up to the task and happy to spend a rainy afternoon talking about density and zoning. Their hosts were urban designer Jonathan Konkol and architect Rick Potestio, and the event was a dry run of the duo’s Dynamic Density process, a new method of accommodating growth which empowers neighborhoods.

I bet you think you know where this is headed.

We’re in Irvington after all, the inner-Portland neighborhood which in 2010, after years of work by neighborhood activists, was put on the National Register of Historic Places. With that designation, “Irvington now benefits from important protections that encourage preserving the area’s character and livability for future generations.”

Offhand, one wouldn’t expect this to be the most receptive audience to a pitch about growth.

Neighborhoods would become Community Development Corporations, making them eligible to receive a portion of the system development charges the city collects from new development.

But Konkol and Potestio think there is a way forward, past the tension between preserving neighborhood character and the need for affordable places to live.

As Konkol says, “It’s not if we grow, it’s how we grow.”

Konkol and Potestio have teamed up to form the ReUrbanist Collaborative, and Saturday’s event was a test to see if their Dynamic Density process was viable. And yes, the test involved a bunch of legos, and a bunch of people who care about their neighborhood, about half of them were affiliated with the board of the Irvington neighborhood association.

Potestio began the day with a presentation about density, zoning and growth. He pointed out that, even without changing a single building in Irvington, the neighborhood population one hundred years ago would have been about double what it is today. That’s partly because families were larger and more people lived in a typical house, but also because our standards have changed. People today want two bathrooms, not one, and they want more space per person to live in. But, in a disconnect between what people want and what is actually getting built, Potestio said “we are right now designing for one-, two-bedrooms, or studios.” We are also in the middle of a housing crisis, he continued, without enough housing production to meet demand. And our local and state governments are responding by undoing decades of growth policy. “There is a lot of pressure to expand the urban growth boundaries, on the precept that more land is cheap land and that we can build affordably by building out. And that argument is being made in legislature right now,” Potestio said.

Both Konkol and Potestio disagree that sprawl is the answer to the housing crisis, and their goal is to increase the housing supply in all neighborhoods — particularly urban neighborhoods well-served by transit — in a way that makes neighborhoods a partner in that growth.

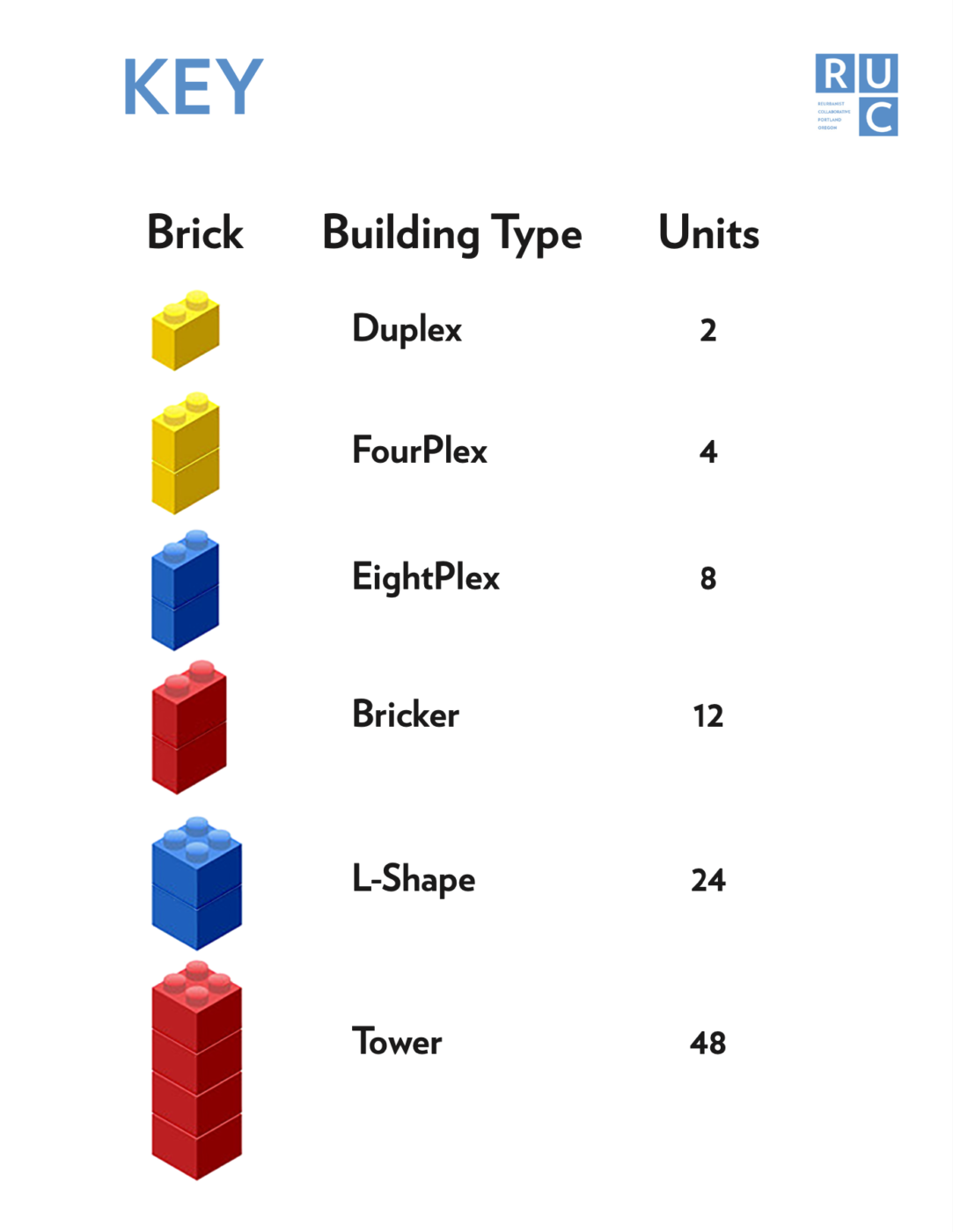

(Source: ReUrbanist Collaborative)

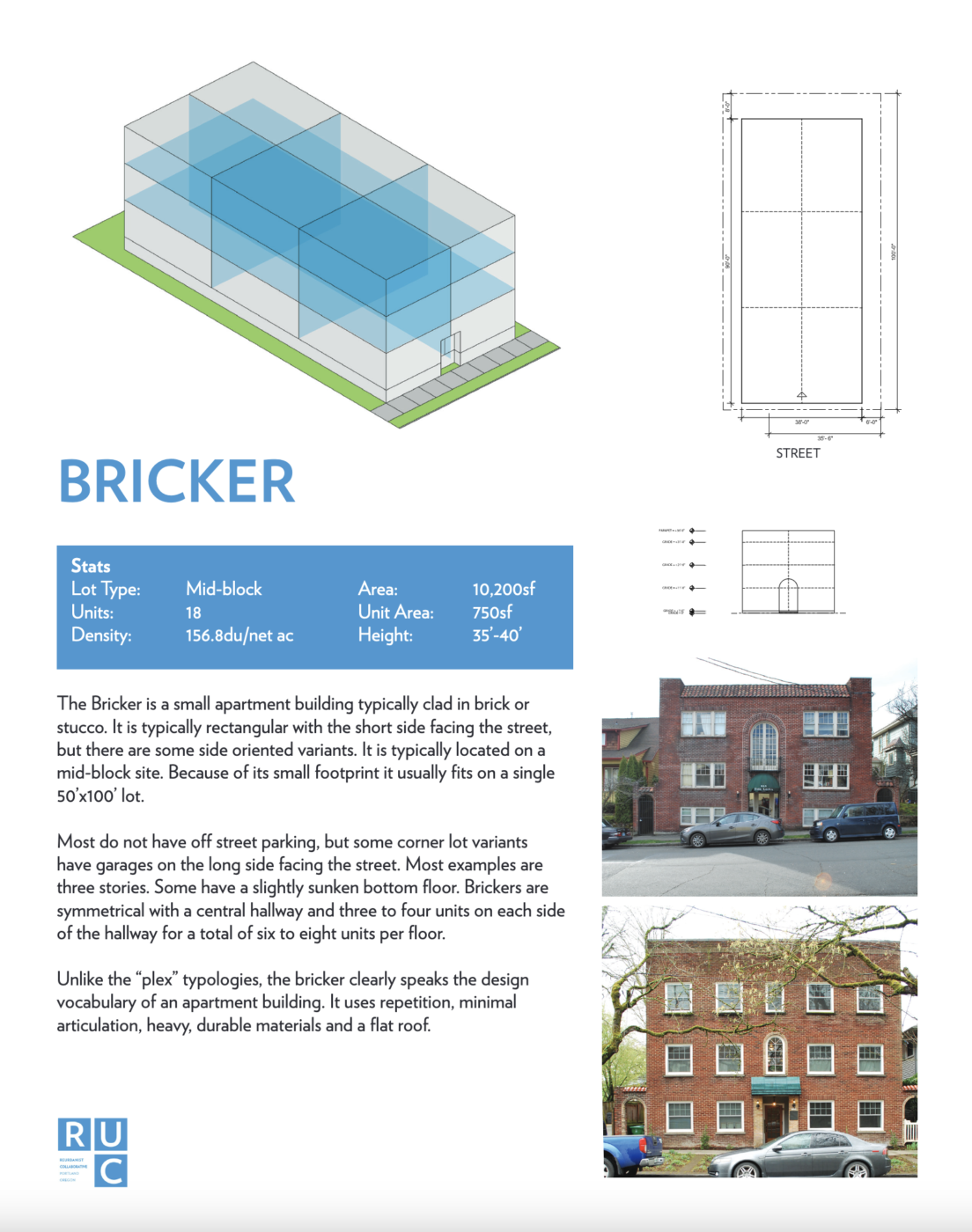

(Source: ReUrbanist Collaborative)We have all heard of duplexes and four-plexes, but what about the cryptoplex and the bricker? Distributed throughout the room were pattern books of traditional building typologies: the twin house, the stacked duplex, courtyard apartments.

With those typologies in mind, the group toured the neighborhood to see examples of them in real life. Upon returning, Potestio numbered participants off into three groups and gave each one a bag of legos representing 600 housing units. There was a catch of course. The collection of legos in each of the bags was not the same, no, no, no, there was a “low-,” “mixed-” and “high-” density bag, each filled with legos representing different types and densities of structures. The Dynamic Density task for each group was to create a granular zoning which would accommodate the additional dwelling types in each bag.

The low density bag was filled mainly with Duplexes and FourPlexes, the high density folks got L-shapes and Towers.

The mixed-density group got an even distribution of the six building types, meaning it had the most diverse set of buildings, and also about an average number of lego bricks—compared to the generous low-density bag, or the meager high-density bag of towers.

And off the three groups went to their tables and maps.

Mixed-density bag

Mixed-density bag High-density bag

High-density bagTo be honest, I took off for a couple hours as the groups worked, but I returned in time for the presentations, and to a room full of intently focused people. Afterward I talked to Konkol a bit about the mood in the room, and he described it as one of “curious problem solving.”

Two participants talk across a soon to be filled map.

Two participants talk across a soon to be filled map.

The final group to present was the table with the low-density bag (pictured at top), and when they were done everybody ended up in a loose circle around their table. The hosts bought a round of beer for participants and we fell into a relaxed conversation about growth. This was my favorite part of the day, informed people thinking out loud, and the conversation was all over the place: low-density infill doesn’t solve the affordability problem because the new units end up costing the same as the single-family house they replace; ground is expensive in Irvington; zoning is exclusionary; the difference between the old Portland Development Commission and its new incarnation, Prosper Portland; the Pearl district was built by local developers; 25% of the units there were built as affordable housing; today, most developers are based out-of-state, an extractive economy.

For me, the day felt like a long monopoly game (that’s a compliment), and I found myself wondering what it was like to play monopoly during the depression — you didn’t have any money but it might have been fun to throw around the fake stuff.

Similarly, this past few years we have seen all sorts of changes to regulations in the name of encouraging housing production. Some of it might be necessary, but it is also true that the housing crisis is starting to feel like a great big fig leaf covering enormous giveaways to the building industry, giveaways that may not adequately increase the housing supply, or make it more affordable. It seems like there’s a lack of vision and a flailing attempt to do something, anything.

In that context, it is kind of nice to have someone ask for your recommendation about accommodating future growth in your neighborhood, and fun to sit around talking about it.

I left off the part about money. A key element of the Dynamic Density plan is that neighborhoods would become Community Development Corporations, making them eligible to receive a portion of the system development charges the city collects from new development. This lets a neighborhood benefit financially from the growth happening within it. Neighbors could then direct their allocation to neighborhood projects, such as a community garden, a new dog park, or beautifying.

Jonathan Konkol summed up the ReUrbanizing sensibility to me with some final words:

“We are stewards of our built environment, watching over it for the next generation. There should be a synergy between preserving what we love about our neighborhoods and growing gracefully.”

— Learn more at ReUrbanistCollaborative.com.