(Photos: Jonathan Maus/BikePortland)

(Photos: Jonathan Maus/BikePortland)The types of wheeled-vehicles used for getting around on our streets these days are very different than they were a decade or so ago. Bike lanes aren’t just used by people on regular bikes anymore: take a look at who’s using Portland’s bike infrastructure and you’ll see all kinds of devices, from Lime e-scooters to large cargo bikes, and even electric one-wheelers.

But as transportation technology has rapidly evolved, bikeway design has largely stayed the same. A new working paper from the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO), “Designing for Small Things With Wheels,” offers tips for city planners looking to bring bike infrastructure into the new era of micromobility.

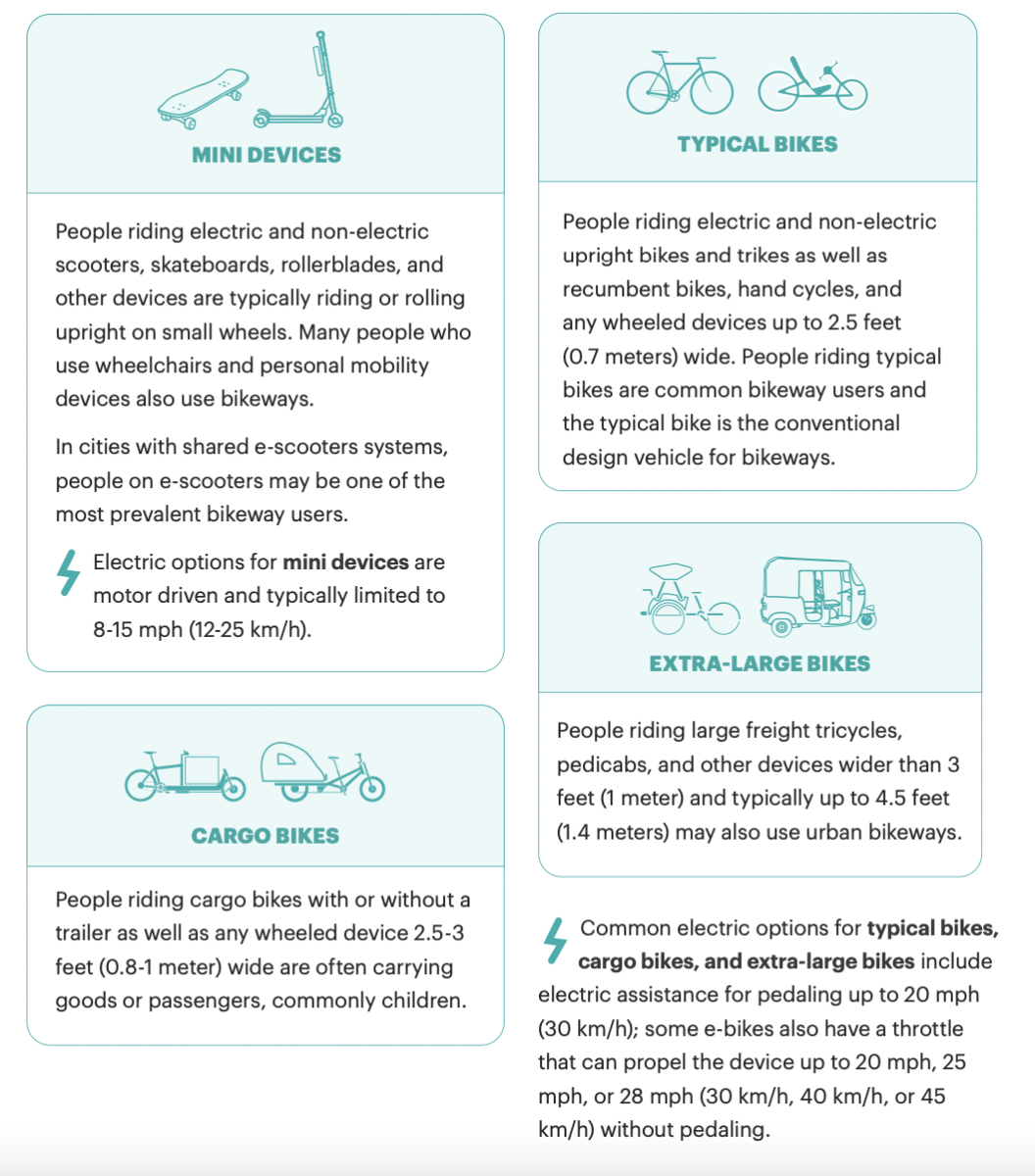

“Rapid growth in cargo bikes and trikes for deliveries and family transportation means that many devices in a bikeway are wider, longer, and have larger turning radii than typical bikes,” the paper states. “E-scooters have smaller wheels than bicycles and handle surfaces, bumps, grates, and gradients differently than devices with larger tires.”

Some people may ask if people riding all these newfangled devices be allowed in the bike lanes at all. Yes, the NACTO paper says: even if an e-bike or scooter can travel faster than a regular one, the person riding it is still vulnerable to car traffic. Design improvements can make it so everyone can travel safely without competing for space.

“In most cases, bike lanes are the best, safest, and most comfortable place for people using the wide array of (often electrified) small things with wheels,” the paper states. “To ensure bikeway design is inclusive of all potential riders — regardless of which wheeled device they ride — designers need to accommodate more people using bikeways with higher speed and size differentials.”

The paper comes up with four key areas where “updated design thinking” is required to accommodate the new breadth of vehicle types: lane width, intersections and driveways, surfaces and gradients, and network legibility.

Lane width

Biking speed varies substantially from person to person, and as electric devices grow in popularity, the range of speeds you might see people using in a bike lane is also expanding. How can we make sure all of those people are able to travel safely?

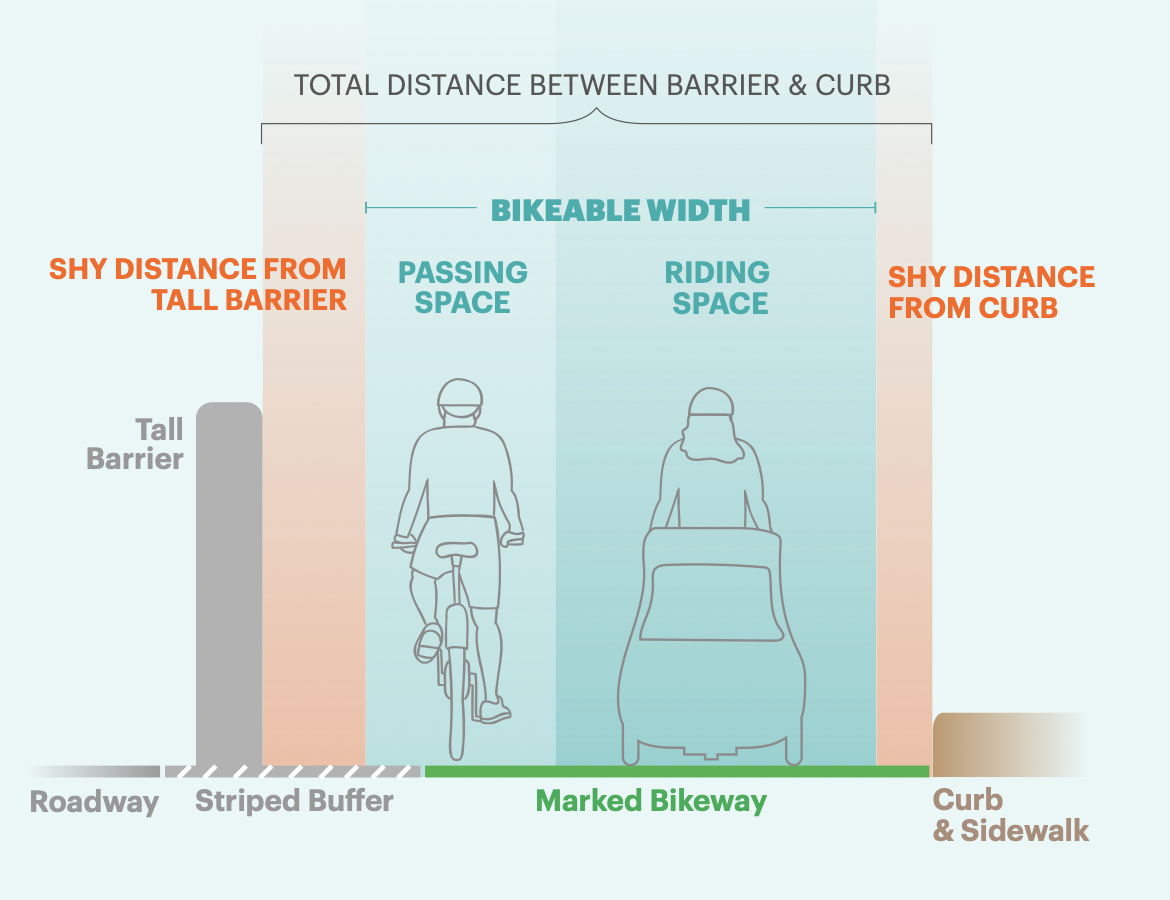

One key way is to address lane width so people can pass each other comfortably in bike lanes, even if they’re riding bigger devices like cargo trikes.

“Wider bikeways can more comfortably accommodate the increase in passing events and the increase in side-by-side riding that comes with higher bike volumes,” the paper states. “Wider protected bike lanes are especially important for children and caregivers, side-by-side riders, people using adaptive devices, and people moving goods.

The paper provides a step-by-step method for determining necessary lane widths, which differs for one-way and two-way bikeways. Ultimately, these calculations will vary depending on who a planner determines is using the bike lanes, but the paper suggests considering the widest device people will use to determine the passing space width and making sure to consider the different between the marked width of a bikeway on paper and actual bikeable width. (Remember the “shy distance”: the “unrideable surface next to a vertical object” because it’s too close to a wall, curb, gutter, etc.)

Using these guidelines, a one-way bike lane accommodating cargo bikes should be 7.5-8.5 feet wide — doubled for a two-way lane. This is quite a bit wider than some of Portland’s bike lanes, including the two-way bikeway on Naito Parkway, which has seven feet of space in each direction.

If there isn’t enough space along the entire bikeway, NACTO suggests ways to make do: “along all facilities, look for opportunities to provide and designate wider passing areas. Uphill passing opportunities can be especially beneficial along facilities where people use devices with and without electric assistance.”

Intersections and driveways

(Source: NACTO, Don’t Give Up at the Intersection)

(Source: NACTO, Don’t Give Up at the Intersection)

Good intersection design is crucial for making sure interactions between people on micromobility devices and people in cars go smoothly. With new sets of wheels in the picture, planners have different considerations to make. The NACTO paper gives three recommendations for designing intersections and driveways, which are to:

“Design enough space for people to wait at intersections” to avoid overcrowding and conflict between pedestrians, bikeway users and motor vehicle traffic, and provide an obvious safe place to wait so people don’t “spill into a crosswalk be forced to wait very close to motor vehicle traffic.” “Allow turning maneuvers and lane shifts at appropriate operating speeds” and make sure turning radii at intersections are “maneuverable by all devices operating in the bikeway.” “Ensure visibility of all bikeway users at intersections and driveways,” which varies “based on motor vehicle speed, driver expectations, and bikeway speeds.” People riding faster devices in the bikeways “necessitate longer sight distances so turning drivers can see approaching riders in time to slow, yield, or stop completely.”Surfaces and gradients

With different sets of wheels come different on-pavement experiences. Things that might be okay to someone riding a regular bike may be insurmountable to someone on a skateboard or scooter with a set of small, dense wheels that don’t absorb shock well. (And honestly, the people on bikes will appreciate smoother surfaces, too.)

“For many riders with small wheels, even slight maneuvers to avoid debris can cause the user to fall, tip over, or lose control of the device. Trash, gravel, snow, ice, and other roadway debris become a major challenge for these smaller-wheeled devices and a considerable nuisance for users with larger wheels,” the paper states.

Some tips for planners: design a “smooth but not slick” surface that has good traction in all weather conditions and consider how to make grade changes more comfortable. (The paper endorses bike-friendly speed bump designs like the ones PBOT is currently seeking feedback about.)

But, as we all know, none of this matters if the roadways aren’t well-maintained. The paper states cities need to “develop proactive maintenance practices to ensure that bikeway surfaces are maintained to a higher degree,” noting that “relatively minor potholes, longitudinal cracks and seams, and other roadway defects can pose a hazard for smaller-wheeled devices.”

Network legibility

The paper references the Better Naito scooter markings as a good example of how bikeway design can show they’re welcoming to a variety of devices. (Photo: Taylor Griggs/BikePortland)

The paper references the Better Naito scooter markings as a good example of how bikeway design can show they’re welcoming to a variety of devices. (Photo: Taylor Griggs/BikePortland)

How do people know which bikeways to use? Wayfinding and network legibility is becoming a hot topic of conversation amongst bike advocates here in Portland, and apparently the concern is relevant across North America at large. The NACTO paper states that “people rely on a combination of formal information and obvious connections when deciding where to ride” and including “comprehensive wayfinding and intuitive, comfortable, and safe transitions between facilities improves the function of the bike network and of the sidewalk network.”

“Signs and markings are not a substitute for good design, but help set expectations for how to use the bikeway. They are helpful for clarifying the variety of ways people can use the bikeway and emphasizing that newly popular device types—like e-scooters and e-bikes—are welcome,” the paper states (using an example from Portland’s own Naito Parkway).

It’s interesting to think about how infrastructure should evolve along with vehicle types. I think much of the backlash to shared micromobility devices like electric scooters has to do with the fact that their adoption and popularity has outpaced infrastructure development in a lot of cases. In a place like Los Angeles, which has rentable scooters all over the place but a limited bike lane network, people are forced to ride on the sidewalks (even though the scooter companies say not to) or the street. This can result in an uncomfortable and dangerous travel environment for everyone.

As Portland prepares to potentially adopt plans like an e-bike rebate program and a cargo bike-friendly freight plan, the city will need to work even harder to make sure our streets accommodate all of these devices. This NACTO paper provides a good framework for where they could start. You can read the full paper here.

Taylor has been BikePortland’s staff writer since November 2021. She has also written for Street Roots and Eugene Weekly. Contact her at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.