(Photos courtesy of the author)

(Photos courtesy of the author)

The writer of this essay asked to remain anonymous because they did not get prior approval from management to contact media. It was submitted as part of a community project to keep BikePortland going while BikePortland Editor & Publisher Jonathan Maus is tending to a family medical emergency out of town and unable to work as normal.

I’ve seen the sun rise more in the last six months than I have in the preceding 46 years of my life. Most days I wake up in the 4 o’clock hour to start my shift as a bus driver for TriMet. The pre-dawn risings began on the first day of training, when I rode my bike to Center Garage, TriMet’s main bus depot off Southeast 11th and Holgate, for a 6:00 am report time. This newfound appreciation for dawn isn’t the only thing I’ve learned in the last six months.

On day three, I was behind the wheel of a bus on public streets with real cars, real pedestrians and real responsibility.

The training program for bus drivers is truly incredible. TriMet is a national leader in operator training, regularly receiving visitors from other agencies. Over seven weeks, trainers teach greenhorns to safely and efficiently navigate a 30, 40, and even 60-foot bus through narrow and often unknown streets, making turns in unfamiliar intersections in the dark of the night with rain-blurred visibility. The learning curve is steep: On day three, I was behind the wheel of a bus on public streets with real cars, real pedestrians and real responsibility. For the first few weeks, I would come home from a day of driving completely mentally and physically exhausted. Suffice to say: When you see “TRAINING BUS” on the overhead display, give that bus some extra room. Even after drivers are on their own, trainers conduct regular “check rides” to ensure they are following safe driving practices. That’s what’s happening when you see a person in a yellow vest standing near the driver.

There is no question of liability or fault. The only question is if an alert driver could have taken steps to prevent the accident from occurring.

The single biggest technique learned during training is to be constantly scanning. I scan my right and left mirrors every five to eight seconds, making sure to register what I’m seeing and how it may affect my operation of the bus. I scan those same side mirrors twice each when pulling out from a service or traffic stop. I’ve been taught to also look over my shoulder in both directions after servicing a stop to ensure a late-running passenger hasn’t slipped into my mirror’s blind spot. The options for maneuvering a bus are much more limited than a car so I scan way ahead down the road for potential hazards like road construction, cars being erratic, or stopped traffic. It’s also critical that I keep an eye on the overhead mirror inside the bus. I check it whenever someone pulls the cord to see which door they are likely to use, or if they have a large load to manage, or have a mobility issue that may affect where I land the bus at the stop. And of course I watch boarding passengers until they find their seat so I can keep a stable platform to avoid any falls. There’s a nearly unlimited amount of scanning and to do it effectively requires my constant attention.

The theoretical result of all this scanning is that we avoid “preventable accidents”, also known as PAs. If I rip off my side mirror on a tree branch, or catch an illegally parked car’s bumper in a turn, or end up being unable to squeeze down a narrow street due to a trash truck riding over the double yellow line, I get dinged with a PA, which can lead to termination. TriMet holds bus drivers to a completely different standard than state law does for driving a car. There is no question of liability or fault. The only question is if an alert driver could have taken steps to prevent the accident from occurring. If this sounds like an extremely high burden of responsibility, it is. Driving a bus is a big deal. A long-time operator once told me that there are no good drivers, just good driving.

When things are going smoothly, it can be really fun to help passengers get where they’re going. Every driver is different but my favorite passengers are the ones who wear a safety vest to catch my eye, wave a hand when I’m approaching to indicate they want a ride, make a little eye contact when boarding, have their fare ready to go, and find their seat quickly. Like most drivers, I don’t care two licks whether or not you pay. I’ve had passengers who paid with a Hop card end up causing problems, and other passengers pitch in to assist riders with mobility issues after asking for a free ride to the Bottle Drop to redeem their cans.

Personally, I appreciate it when passengers put a few coins in the fare box, or pleasantly ask for a free ride. Most drivers are happy to provide a free ride—we’re going that way anyway—so long as you acknowledge the graciousness. (Fare enforcers can appear anywhere, on any line at any time, so you ride at your own risk.) I deeply appreciate the opportunity to have a micro-relationship with everyone and often find that the free riders are among the most helpful in managing a busy bus. Fares are somewhere around 20% of TriMet’s annual revenue so we are taught to focus on ensuring an enjoyable and efficient ride for every customer rather than burning time arguing with someone about a fare. We have a button on our system to record a “fare evasion” and although that data could be used to target fare enforcement missions, it’s mostly used to record ridership counts—a critical data point in securing state and federal funding.

Don’t bother trying to reuse yesterday’s day pass, or feigning ignorance when your Hop card balance is at zero. Just ask for a free ride.

Don’t bother trying to reuse yesterday’s day pass, or feigning ignorance when your Hop card balance is at zero. We can see those little cheats coming before you even get on the bus. Just ask for a free ride.

Another thing I like are all the thank-yous and waves when riders leave the bus. I see your hand waves from the back door when you have your headphones on. I hear your little mumbles of thanks when you’re de-boarding in the middle of a pack. I notice your smiles as you leave through the front door. I don’t often respond, but I see you. I don’t often respond because managing newly-boarded riders, making sure everyone is off who wants to get off, and merging back into traffic is the most intense part of the job—often requiring one hundred percent of my concentration to get it done completely safely with a focus on speed to stay on schedule.

What I don’t see and hear is what happens in the back of the bus, up the steps. Or on the left side behind the driver’s cab. If you are getting bad vibes, or feel uncomfortable with something, or just don’t want to miss your stop, come up to your driver during a stop and say something. If you don’t want to tell your driver, call 503-238-RIDE. As long as the bus isn’t moving, I love helping passengers. Sit on the curbside seats ahead of the rear door so I can keep an eye on you, or call out your stop when it’s coming.

I honestly think that riding the bus is a safe and enjoyable thing. I’m not speaking as a TriMet representative here. I’m sure you’ve heard stories about assaults on drivers and people in a mental crisis making everyone else uncomfortable. And they’re all true, for sure. The bus is a slice of our broader society, nothing more and nothing less. In my six months, I’ve never really felt uncomfortable, for whatever that’s worth to you. And I think my passengers generally enjoy riding the bus.

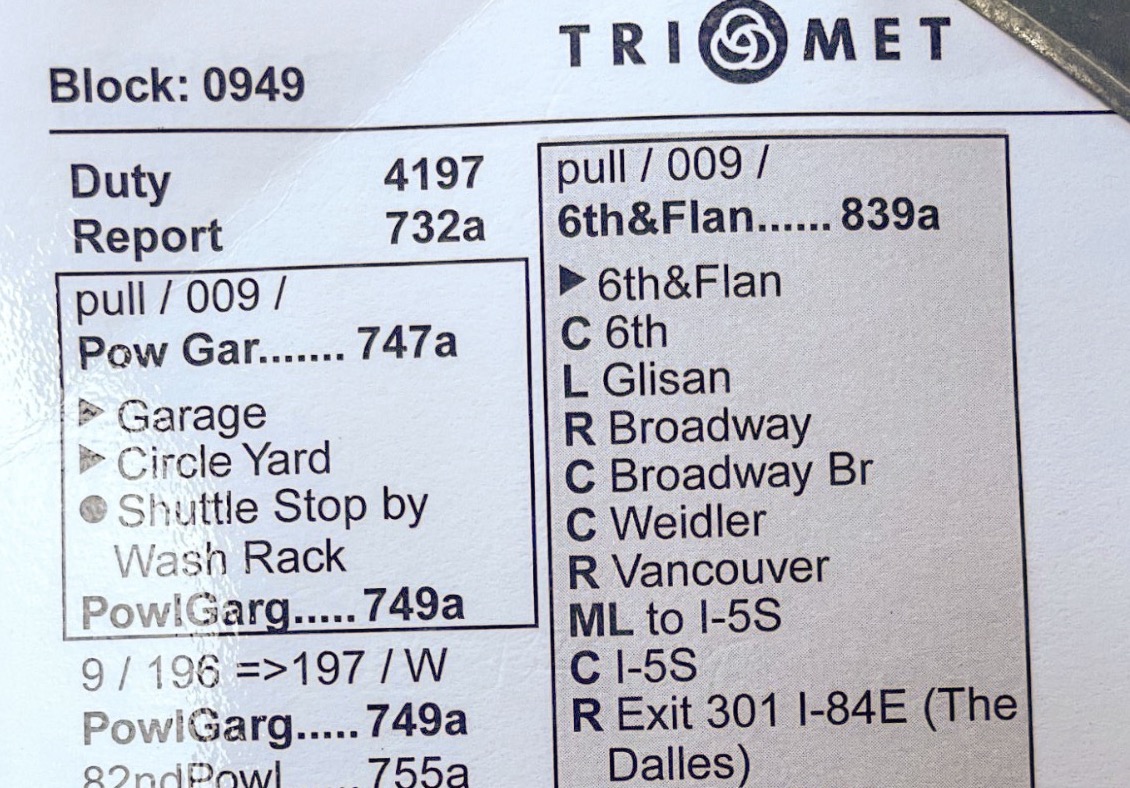

While I love the tiny relationships I build with regular passengers, they all eventually come to an end. Every three months, all bus operators have the opportunity to sign up for a different work schedule. Some drivers choose to run the same route every day for three months while others work the “extra board” which is a bit of a daily lottery to fill in for buses that don’t have a driver. Some routes never get assigned a permanent driver which means a new driver runs it every day. I rarely work the extra board, but some operators love the variability and do it for years at a time. Instead, I work “vacation relief,” which means I fill in for other drivers on a weekly basis while they are on vacation from their regular work. It’s a great middle ground between getting bored doing the same thing every day and the uncertainty of being on the extra board.

TriMet makes a lot of effort to have extra board operators on standby. But sometimes there aren’t enough drivers available for a route and it gets canceled. The driver shortage is real. In 2019, there were over 1000 drivers and service levels were growing. Then came COVID. Our excellent union, Amalgamated Transit Union Local 757, was able to avoid any driver layoffs but many drivers took the pandemic as an opportunity to retire or change careers. Now we are down to about 800 drivers, so it makes sense that service levels have suffered.

At current rates, it will take years to recover to pre-pandemic levels of service.My training class started with 28 people. Only 20 made it through the seven weeks. And with something like 30-50% of new drivers quitting or being let go within the six-month probationary period, TriMet isn’t churning out new drivers too quickly. (Oh and that juicy $7,500 bonus you’ve seen plastered across our in-house ads? It’s paid out over three years.)

The back doors suck, let’s just be honest.

There are a lot of different buses to get used to. My favorite ones aren’t the newest. That might sound counterintuitive but many drivers I talk to agree. We like the 3500 and 3600 series buses because the rear doors close the fastest after a passenger gets off. The 4200 buses have a backup camera, but I’ve got worse problems than not being able to see behind me if I need to go into reverse.

The 4000 series models and up have intense red interior lights.They are supposed to help us keep our night vision, but I also think it’s a cool effect.

One thing I wish was standardized is the rear door opening action. Most buses have a motion-sensor eye above the door, by the green light. But some doors have touch-strips on the vertical door handles that you push to open. If I had a nickel for every time someone asks me to open the back doors when they’re already open, I could quit TriMet. I’ve found that the best technique to get the motion-sensor to see you isn’t to push on the doors themselves, but to gently push your whole forearm horizontally across the door. Small and quick stabbing motions with your hands sometimes aren’t seen by the eyes. So then you yell, “Back door!,” and I mutter, “It’s already open, just push!” and then you push and it finally opens (which makes you think that the doors finally opened because of something I did).

The back doors suck, let’s just be honest. I wish I could open and close all the doors all the time like on the green FX buses.

If something breaks, or a situation gets bad inside or outside the bus, we can summon help from a supervisor. They are the people driving around or parked at Transit Centers in the little white SUVs. You can tell a supervisor when they’re not in their cars by their light blue shirts. They can solve problems with unruly passengers, do light mechanical fixes, help out us drivers if we are having personal problems, help move things along if we are running late, and handle service disruptions like MAX trains breaking down or road construction interrupting bus stops.

I’ve learn a lot and I enjoy driving a bus much more than I thought I would. I’m now a bigger advocate for buses than ever. If you haven’t ridden a TriMet bus recently, maybe consider giving it another try. And keep up the thank-yous, even if you don’t get a reply. I’m probably scanning my mirrors, watching people move around the bus, and trying to stay on schedule.