Cycling News & Blog Articles

Let’s build it! Portland’s Protected Bike Lane Design Guide is finally out

The new guide tells us we could build a physically-protected lane (like the one in the graphic on the left) on East Burnside between Couch and 11th for as little as $224,000.

(Photo: Jonathan Maus/BikePortland)

At long last, Portland has an official guidebook to build out its protected bike lane network.

If you’re feeling a bit of déjà vu, that’s because we excitedly shared this same news back in June of 2018. But for some reason, after it came out in draft form, the guide was scrubbed from the Portland Bureau of Transportation website pending more internal reviews. Many advocates were excited when the guide was set for City Council adoption in September 2020, but (former) PBOT Commissioner Chloe Eudaly and PBOT leadership scuttled that plan at the last minute due to concerns over racial optics. I’ve been hounding PBOT ever since about when it would be released, and then lo and behold, I just happened to stumble upon it on their website a few days ago. It looks to have been finalized and published in May 2021.

More of the backstory here is that the PBOT has not built enough protected bike lanes to entice the masses to ride. Portland has built just 38 miles of protected bike lanes — less than four miles per year — since 2010. One of the reasons we’ve been given for this glacial pace is that PBOT staff (engineers, planners, project managers) haven’t had an official guidebook to work from. If you know anything about how government works, you know that in order for things to get built, staff must have guidance to not only help them understand what to do, but also to absolve themselves of legal and/or political fallout if things don’t turn out well.

In the U.S., engineers are trained with guidebooks from the Federal Highway Administration and state DOTs, and have only recently been using a more progressive one created by the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO). But none of those resources have the detailed, hyperlocal knowledge necessary for city staff to confidently implement protected bike lanes right here in Portland.

That’s where the Portland Protected Bicycle Lane Design Guide (PDF) comes in.

Why does this thing matter? Because like I shared above, it gives city staff an authoritative source for decision-making. This guide offers detailed cross-sections, data, and insights that give engineers, project managers, and planners the ability to simply plug-in their street characteristics and see what type of protected bike lane design is feasible, how to build it, what to consider when doing so, and how much it’s likely to cost.

Speaking of cost, the detailed breakdowns of how much money it will take to build a protected bike lane network are one of the coolest parts of the guide. PBOT says costs range from $73,000 per mile to build parking-protected bike lanes (on one-way roads) to $1.1 million per mile to install concrete island-separated bike lanes on a two-way road.

Here are some other key nuggets in the 125-page guide:

Advertisement

— PBOT addresses maintenance issues by saying they are still trying to find a sweeper that can get into five-foot wide protected bike lanes (the narrowest variety). The guide also addresses access considerations for mail delivery, garbage bins, and delivery vehicles.

— The guide says PBOT’s preferred width of a one-way protected bikeway is 6.5-feet of clear space in the “bicycling zone” (not including a buffer or necessary shy distance, both of which are explained in detail). 5-feet is the absolute minimum and should only be used where there are less than 150 riders per hour at the peak. If there are more than 750 riders per hour, the preferred width shoots up to 10-feet on a one-way street. For bidirectional bike lanes, PBOT sets a minimum of 10-feet and a maximum of 16-feet.

— As frustrations mount about the use of cheap and frail plastic wands, some of you might find comfort that PBOT acknowledges the issue in the guide. “Jurisdictions across North America that rushed to install protected bicycle lanes with delineator posts are replacing them with more permanent materials,” it reads. “Delineator posts may require frequent maintenance if they are hit often. For example, some of Portland’s existing delineator protected bicycle lanes require replacement of approximately 10% of installed posts every six months.”

— One detailed I loved to see was how PBOT understands the problem with low-hanging tree branches. Because many protected bike lanes create a bicycling zone where there typically isn’t one (next to the curb), they state in the guide that, “once [the curb zone] becomes a bicycling zone, low-hanging branches and other intruding foliage present a hazard to people bicycling.” PBOT says trees must be cut to a minimum height of 11-feet above the roadway.

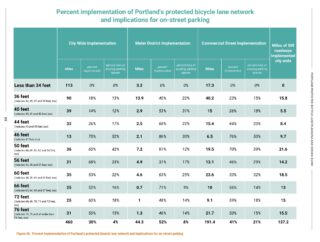

— Parking removal gets a lot of attention since it’s often the #1 controversy when building protected lanes. The guide has a detailed spreadsheet (above) about how much car parking is estimated to be needed to build all the different types of designs. To put it into perspective, PBOT estimates that if they build just 30%, or 137 miles of the 460 total miles of protected bike lanes Portland needs, it would only result in a loss of 4% of the overall on-street space currently used for parking cars. They also break that number down for meter districts, where half the proposed protected bike lanes (about 44 miles) would result in a loss of 8% of metered parking spots. And in commercial districts, if we built 41% of the 191 miles of protected bike lanes called for in our existing plans, it would result in a reduction of 21% of existing on-street parking spots.

— Back to costs, if PBOT built out a majority of these 137 miles of protected bike lanes with plastic delineator posts, it would cost just $57 million. To retrofit street with 4-foot wide concrete traffic separators, the cost is about $1 million per mile. These figure are “fully loaded”, meaning it has a 2.5 multiplier over construction costs that takes into account design, administrative staff, and so on.

According to League of American Bicyclists Policy Director Ken McLeod, guides like this one are “rare”. He says none of the other top cycling cities in America like Madison, Boulder, or Davis have such detailed operating instructions for protected bike lanes. Their plans usually just reference national guidebooks like NACTO’s Urban Bikeway Design Guide.

There’s a ton of great information in this guide and we hope it becomes a powerful tool for both PBOT staff and advocates alike. We have just removed one of the main excuses for not building protected lanes. So let’s get to it.

One last thing: The completion of this guide would be a great excuse to get cycling some attention in City Hall. I’ve asked PBOT if they plan to present it to council for adoption and will update this story when I hear back.

If you’re wonky and you know it, click here for the PDF.

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.